I have picked up this book for my summer 2025 reading:

Coggan’s More: A History of the World Economy from the Iron Age to the Information Age (PublicAffairs, March 24, 2020) is a brisk, 500-page journey through ten millennia of commerce, technology, and finance. Coggan, a long-time Economist columnist, argues that humanity’s ability to create ever-denser networks of exchange—of goods, money, ideas and labour—is the thread that links obsidian traders in the Fertile Crescent to today’s cloud-computing giants. Each chapter shows how new “connections” such as coinage, credit, railroads, or the internet unlocked fresh waves of specialization and productivity, producing the “more” of the title.

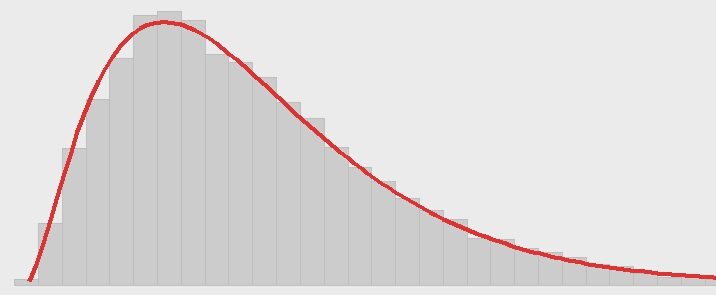

Alongside this optimistic arc, Coggan stops at the roadblocks: the Black Death, seventeenth-century tulip mania, the Great Depression, decolonisation, the oil shocks and the global financial crisis. His narrative makes clear that economic growth is neither smooth nor inevitable; it is punctuated by systemic shocks, wars and environmental constraints that force societies to adapt or collapse. By weaving demographic change—urbanization, rising longevity, shifting fertility—into the story, he shows how population trends both drive and respond to economic shifts.

For my actuarial students, the book offers an unusually accessible macro-economic backdrop to the models they build. Life insurance companies, pension funds and risk managers routinely project interest rates, wage growth and inflation decades ahead; seeing how those variables behaved over centuries grounds abstract stochastic assumptions in historical reality. Reading about the long-run decline of real interest rates after the Industrial Revolution, or the post-war inflationary burst, sharpens intuition for scenario generators and capital-adequacy stress tests.

The vivid accounts of crises provide concrete case studies of tail risk—low-frequency, high-severity events that lie at the heart of solvency modelling and enterprise risk management. Coggan’s treatment of the Black Death, for instance, illustrates mortality shocks; his discussion of the 1929 crash illuminates asset-liability mismatches and liquidity spirals; the 2008 episode highlights interconnected counter-party exposures. Linking these stories to extreme-value theory or capital-model validation exercises makes the statistics feel far less abstract.

Finally, Coggan’s clear, journalistic prose is itself a lesson in communication. Actuaries often translate dense technical results for boards, regulators, and clients; studying how More distils complex systems into engaging narrative can improve their own explanatory craft. The closing reflections on inequality and climate change also remind future professionals that today’s risk landscape extends beyond spreadsheets to environmental, social and governance questions that rating agencies and regulators increasingly expect them to address. In short, while More is not an actuarial manual, it furnishes the historical perspective, risk awareness and storytelling finesse that help turn technical modelers into well-rounded risk professionals.

I hope you enjoy the book!